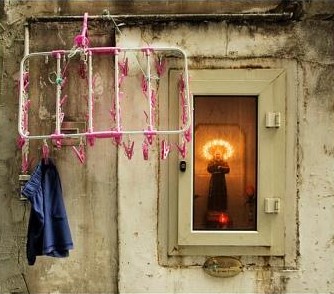

In a previous post, I discussed the role of relational conversion via religious institutions, making the argument that religion to a great extent has succeeded in making the invisible but watchful presence (see also the post Wrapt in a brown mantle) that is the relational world codified and organised – made it visible. The pomp and ceremony of religious rituals act as a vehicle for the publicising and regimenting of relationality, taking the sting out of relational confusion while contributing a whole set of other anxieties manifested as God or variations on the same theme. What s/he giveth in one hand, taketh away in the other …

But arbitrary judgement by peers provides no contest to the absolute judgement of a supreme being, a being that is free from the shackles of earthly desire. To the victor go the spoils and it could be argued that, via this victory, religion in its various guises has tamed the beast that is relationality. It makes sense: what else on earth could offer a defence against the stormtroopers of the relational world – guilt, shame, pride, honour, sacrifice, belonging, acceptance, forgiveness, resentment? The intersubjective nature of relationality stood no chance against the pulverising certitude of the absolute and universal. No wonder solace is sought in sanctity – a benign and simple form of social order always preferable to the ever vigilant world of Dirty Looks. The rules and regulations of religious belonging are literally a godsend to those who have to live in a godless and relativist world of arbitrary acceptance/rejection and approval/condemnation.

In the same post I also made the argument, contrary to Sartre, that religion (but not death) can offer some kind of exit from the judgements of others. At the same time, it is not exactly clear if the choice between salvation and damnation has ever quite escaped its relational roots. These days people are quick to judge themselves, establishing our own judgement day as the deathbed of common imagination – the final reckoning of a life lived, well or not. Who wants to arrive at their endgame dissatisfied, resentful and full of regret at opportunities missed? But this deathbed judgement of popular imagination exists in an awkward relationship with its religious counterpart. The salvation and damnation to be experienced at the pearly gates was absolute and final, while the retrospective earthly accounting of oneself can never compete – the criteria for judgement a confusing mix of the sacred and the profane.

But regardless of version, the principle is the same: judgement will follow you right through life – it is only the choice of critic that is under our control.