Prensky, somewhat incredulous at academia’s critical response to the Digital Native, recently claimed he intended his signature concept to be used only as a metaphor (see this book for details). As I implied in my previous post, it is not an empirically verifiable concept; however this hasn’t prevented its academic investigation.

The research addressing the Digital Native, to enable a testable hypothesis, has constructed the concept of ‘savvy’. Hargittai, a high profile critic of the Digital Native in the USA for example says:

“Assumptions prevail about young people’s inherent savvy with information and communication technologies (ICTs) ” (Hargittai 2010, p93)

Her intention is an “empirical test of assumptions about the supposed inherent savvy of the so-called ‘‘digital natives.’’ (Hargittai 2010, p93)

“While popular rhetoric would have us believe that young users are generally savvy with digital media…” (Hargittai 2010, p108)

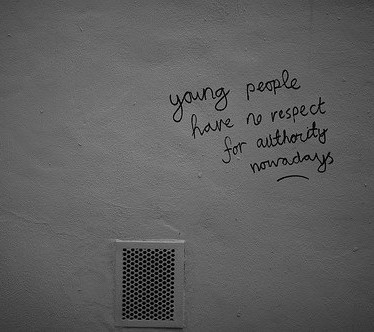

Bennett & Maton (2010, p321), Cheong (2008, p771), Brouwer (2003, p20) among others also use the word “savvy” as an iconic representation of their difficulty with the Digital Native. Yet, Prensky himself never mentions savvy. In fact, if we understand savvy to be synonymous with critical thinking, Tapscott, one of Prensky’s acolytes, says his Net Generation is not savvy. The problem is the word savvy has many cultural connotations and these authors above never explicitly define it. “Savvy” becomes a contrived entry point into the problematisation of youth online without ever being fully explained or justified.

I understand this then as another skirmish in the Foucauldian struggle for the truth. Foucault’s concern was not with the practice of science but the way it is interpreted and deployed. From his perspective, the language used by the scientific community is discursive. The use of technical language to describe young people’s relationship with technology sets out an ‘epistemological space’ for social scientists – it is a space where scientists are equipped to know best. In other words, knowledge is produced, that is, constructed, through disciplines, which are themselves institutionally grounded bodies of discourse that constitute what can become objects of knowledge and who has authority to speak about them (Foucault, 1980).

The Digital Native is a non-scientific term that has crept into spaces the academy should or wants to occupy in our culture. The Digital Native is not an officially sanctioned object of knowledge; it has duly been denounced within scientific discourse. The academy’s reaction to it is a slap-down putting Prensky and his pseudoscience in his place however, in doing so, the deployment of words such as “savvy” can create more problems than they solve – Huw Davies

References

Bennett, S., & Maton, K. (2010). Beyond the “digital natives” debate: Towards a more nuanced understanding of students’ technology experiences. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 26(5), 321–331. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2729.2010.00360.x

Brouwer, S. (2006). They might be gurus. Teacher Librarian, 34(1), 18–26.

Cheong, P. H. (2008). The young and techless? Internet use and problem solving behaviors among young adults in Singapore. New Media and Society, 10 (5), 5(10), 771–791.

Hargittai. (2010). Digital Na(t)ives? Variation in internet skills and uses among members of the “Net Generation”. Sociological Inquiry, 80(1), 92–113.

Another interesting post. I like how you used Foucault here and I couldn’t help but thinking about what Habermas would say about the use of “digital native” and “savvy”… surely something about validity claims 🙂

Thanks for the feedback – I haven’t looked at Habermas in any depth and think maybe I should.