Well in terms of modern social theory, quite a lot it seems. I made this point in my recent edited collection Social theory and education research, when talking about his influence on Bourdieu, Habermas, Derrida and Foucault. Yes, the influence is variable depending on the author, but it’s there, and it’s telling:

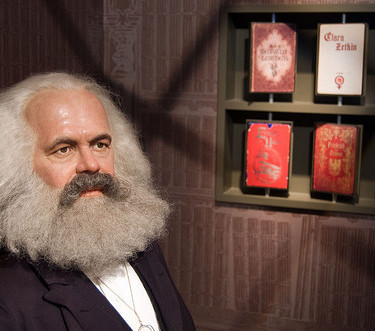

Marx was a pre-eminent social theorist in his own right, his ideas casting a considerable shadow over debates in modern social theory. A great deal of this theory owes some kind of debt to Marx’s concepts of capital, class and exploitation, and his re-workings of post-Enlightenment notions of political economy and liberal democracy. This is clearly evident in the work of Bourdieu, for example, whose work on cultural and social reproduction saw him cast as a neo-Marxist, his ideas helping to fill in some of the blanks in Marx’s historical materialism (especially around the role of culture) (Fowler 2011). Marxism is a key starting point for Habermas, a figure strongly associated with the Frankfurt School of Critical Theory, which included in its ranks (neo)Marxists such as Erich Fromm and Herbert Marcuse (Kellner 1989). Habermas’ key work The theory of comunicative action (1984, 1987), was at base a project designed to reconstruct Marx’s theory of historical materialism, in order to provide (in Habermas’ opinion) a better diagnosis of the problems facing late capitalist society (Murphy 2009). Foucault, who later in his career moved decisively away from Hegelian dialectics, was ‘considerably influenced by Marx’ early on (Best 1995, 87), his first book Mental illness and psychology (Foucault 1976) was immersed in Marxist concepts of alienation and contradiction. Even Derrida, whose post-structuralist approach to deconstruction could never be confused with Marxian political economy, argued at one stage for a return to Marx, publishing his famous text Spectres of Marx to a bemused academic world – the editor arguing that for Derrida, ‘deconstruction’ ‘always already moves within a certain spirit of Marx’ (Magnus and Cullenberg 1994, x).

I go on in the book to argue that the legacy of Marx lives on in another important way – in the significance attached to the nature of power in modern society (see also my current blog series on power). What I also mentioned (but maybe should have made more of) was the lessons that can be learnt from how key social theorists either built on and/or reshaped Marxist concepts (Bourdieu, Habermas), or made decisive breaks with Marx (Derrida, Foucault). Leaving aside the complexity of the arguments, the fact that major social theories (and Marxism was certainly one of those) can either be reshaped or dispensed with, illustrates the fragility at the heart of social theory. No theory is ever set in stone – precisely because it is a theory. It may not have appeared as such to communists and fellow travellers in the 20th Century, but the theory of historical materialism was as fragile as they come. But that didn’t prevent it from ruling the intellectual roost for so long. Then the bubble burst, the result being that the intellectual pulse of the humanities and social sciences feels very different today than it did 30 years ago.

But having said that, the current set of critiques of neo-liberalism (prominent in critical education research for example) seem to me to be heavily indebted to Marx – ‘commodification’, ‘privatisation’, ‘marketisation’ and so on. Maybe the spectre of Marx has returned – or has it?

I would recommend to anyone who would like to understand modern capitalist society to become scholars of Marx via David Harvey. You can be part of his community of Marxist inquiry online http://davidharvey.org/reading-capital/

I would assert that in order to understand now, you have to understand Marx. David Harvey can bring this endeavour to life having lectured on Capital for 40 years.

That’s a very useful link, many thanks – I didn’t realise they were all up online and for free! I’d recommend this site if you want to get to grips with Capital. One of my Doctoral studies modules was wholly devoted to Capital, but of course we could only cover small sections in that time. Pity the site wasn’t up back then, Mark