Futures and fractures in feminist and queer higher education

Special issue edited by

University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK

Introduction

Futures and fractures in feminist and queer higher education is concerned with educational futures, in the sense of the futures of higher education (HE) as well as the future-orientated subjectivities implied in HE practice. These futurities are not homogenous, linear or certain, but rather can be uncertain, stratifying, precarious, or in-between. Educational futures are often imaged as universal, without naming their located specificity: your educational future may not be mine. Universities' pasts, presents and futures often rely on and reproduce sexist, classist, racist, colonial relations and in a landscape of 'internationalization' – of mobility for some staff and student bodies – these relations seem reconfigured rather than resolved (Arday & Mirza, 2018; Bhambra et al., 2018; Leathwood & Read, 2009; Mahony & Zmroczek 1997; Waller et al. 2017). 'The Future' is also bound up with unreliable enlightenment promises of progress (increasingly efficient–excellent–exceptional institutions) and neoliberal meritocracy (upwardly mobile responsibilised, entrepreneurial competitively-achieving individuals) (Addison, 2012; Taylor, 2014; Taylor & Scurry, 2011).

Asking how to repeatedly re-imagine and prefigure educational futures more queerly, cognizant of persistent and emerging fractures, this Special Issue aims to continue the established queer feminist project of troubling some of the uneven or over-stated promise of 'our futures' (Edelman, 2004; Dinshaw et al., 2007; Muñoz, 2009). In addressing the futurity and fracturing of HE we explore possibilities of doing queer feminist education, as well as the blockages and ruptures involved. We set out to extend interdisciplinary debates on social change in HE, particularly as marked by gender, sexuality, and their intersections (Taylor, 2012), situated alongside a body of feminist academic and activist work (Taylor & Lahad, 2018; Thwaites & Pressland, 2016).

It is well documented that higher education is characterized by, and maintains, intersectional 'inequality regimes' (Acker, 2006). There is a growing body of evidence on the whiteness of curricula, disciplines, and universities, and on the university as border control (Ali et al., 2010; Andrews, 2015; Dear, 2018; Mahn, forthcoming; Mirza, 2015). Concurrently, 'diversity' is increasingly mainstreamed in higher education policy and governance, figured as a desirable, promotional characteristic of the neoliberal, 'international' entrepreneurial university (Mirza, 2006; Puar, 2004; Taylor, 2013). Yet such institutional commitments are 'non-performative' and do not bring about the diversity they name (Ahmed, 2012 a, b).

In this context, the impetus for this Special Issue emerged from the Educational Futures and Fractures conference organized by one co-editor, Yvette Taylor, at the University of Strathclyde (Glasgow, Scotland) in February 2017. Amongst other questions it asked, what, who and where is the future of Higher Education? The conference bought together speakers from across and beyond the UK, including a keynote from Prof Rowena Arshad OBE, responding to and extending this question. Topics included student and staff transitions and (im)mobilities, the reproduction of inequalities across time and space, and the teaching practices, politics and activism which might respond to and resist such stratification. During and after the conference we continued asking questions, such as what queer feminist educational futures can be claimed and forged amidst entrenched intersectional educational inequalities? As these inequalities are fractured through institutional stratification, workforce casualisation, and a marketised, entrepreneurial sector fostering cultures of performativity, metrics, and audit, what kinds of practices, pedagogies, understandings, and connections are necessary for feminist and queer educational futures?

Since the conference took place, significant developments in the UK HE landscape have underscored the urgency of these questions. In February and March 2018 members of the University and College Union (UCU) took part in an unprecedented 14 days of strike action, over proposed changes – and real terms reductions – to pensions with the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS). Involving academic and professional service staff, the sustained industrial action sharpened our attention to the everyday fractures that shape work in higher education. Our out-of-office automatic email replies stood-in for our academic presences, and articulated our (partial) absences from work: Please note that I am currently taking action short of a strike as part of the University and College Union's (UCU) industrial action to defend our right to a fair pension. Response times may be slower for the duration of the dispute, especially outside of normal working hours. Meanwhile lively discussions over the conditions, limits, and possibilities of academic labour – and academic activism – continued on the picket lines and in emergency UCU branch meetings.

The issue of pension reductions was refracted through workforce casualisation and the growth in zero hours contracts alongside temporary, insecure short-term positions, as well as contested distinctions across career categories. Union members grappled with the uneven distribution of the effects of USS pension changes across internal university hierarchies, between academic and professional staff, for early career academics, and across the gender pay gap. Pensions and precarious work are gendered issues, marked by familiar intersections of class and race in the structure of academic pay and promotions. The strike highlighted the surveillance of migrant workers in higher education, which the university is complicit in enforcing, and restrictions of the right to take strike action, particularly for staff on Tier 2 visas (UCU, 2018). The dynamics of the pension dispute traced the fault-lines of hierarchical distinctions between UK HEIs, as 'universities' became conflated with 'pre-92' institutions and as the role of elite institutions seeking to leave the USS scheme was uncovered (Adams, 2018).

Alongside contemporary feminist scholarship that analyses and reflects upon the conditions and limits of academic labour (Acker & Wagner, 2017; Gannon et al., 2015) this Special Issue is located in a particular moment. The times we write in are not severed from past university structures or subjects (Skeggs, 1995), but we do exist in a time of renewed vulnerabilities, pressures and risks. Such risks include departmental closures, downsizing, and redundancies amongst which academics are 'constantly pressured to become successful and efficient fundraisers, produce quantified results, and follow the logics of… supply and demand' (Taylor & Lahad, 2018, p. 2). At the same time managerialist 'technologies of audit' (Sparkes 2007, p. 527) and regimes of performativity (Ball, 2003) proliferate, including the UK Research Excellence Framework (REF), the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF), the National Student Survey, 'performance enhancement', 'development', and 'accountability' reviews, citation indices, impact factors, and annual university rankings.

Queer and feminist academics have long attended to the politics of work, and there is an emergent, growing body of research on academic labour. These literatures document the exhausting work of making space for feminist and queer scholarship (see Pereira, 2016, 2017). There is endemic 'chronic stress, anxiety, and exhaustion' (Gill & Donaghue, 2016, p. 91) arising from the intensification and acceleration of work in the 'greedy institution' (Hey, 2004). Here academics are 'time squeezed' into doing as much work as possible in as little time as possible (Southerton, 2003); 'stretch[ing] the week and themselves' (Taylor, 2012, p. 264), 'working harder and sleeping less' (Acker & Armenti, 2004, p. 3), and becoming 'too tired to think' (Pereira, 2018). Here academic entrance, arrival, and success can become permanently deferred (Taylor, 2014) to an imagined future, just as everyday 'work goals' become an 'ever-receding horizon that cannot be reached' (Pereira, 2016, p. 106).

Queer feminist, feminist and queer scholarship is ambivalently located in relation to these dynamics, and in relation to each other, with at times 'uneasy alliances and productive tensions' between feminist and queer theories, epistemologies, and pedagogies (Leigh, 2017). While both fields, and their combination, can be understood as activist, political projects, and 'critical intervention[s] in the academy', seeking 'not just to generate more knowledge but also… to question and transform existing modes, frameworks, and institutions of knowledge production' (Pereira, 2012, p. 283), there is variation and conflict within and between different feminist and queer approaches to scholarship. Feminist and queer theory and practice can range from anti-capitalist, anti-state, anti-carceral, and decolonial commitments to liberal and neoliberal forms which embed exclusionary politics in their activism (Emejulu, 2018). 'Queer feminist' can articulate disruptive educational subjectivities, compared to institutional approaches to, for instance, gender equality and LGBT+ 'inclusion' and the re-capture of the subversive potential of gender and sexual dissidence.

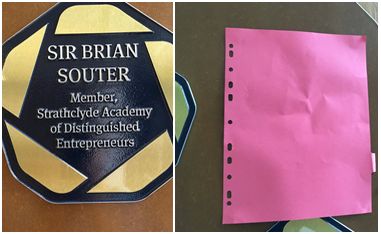

Queer, feminist, and queer feminist scholars occupy an awkward position in the university, which promotes itself as 'diverse' and 'inclusive' and in which queer and feminist presences are both 'celebrated' and silenced (Taylor, 2013). We write this introduction from an institutional context in which the university simultaneously hoists a rainbow flag 'with pride' and displays a plaque honouring Brian Souter, as a member of the 'Strathclyde Academy of Distinguished Entrepreneurs'. Souter funded and publically led a campaign to keep Section 28/2a[1] prohibiting the 'promotion' of homosexuality in schools and other public bodies (BBC, 2000, Rahman, 2004, Taylor, 2005). During another conference hosted at Strathclyde – The Sociology of Religion 2018 – Yvette, having delivered a keynote on Queer Religious Youth, noticed the plaque and worked with other delegates to temporarily cover it up.

Images by Yvette Taylor

The ongoing histories of making space for feminist and queer scholarship underscore such awkward positions and uncomfortable implications, as with how the re-positioning of students as consumers allowed a 'paradoxical' expansion of Women's Studies via the rapid growth in student numbers (Skeggs, 1995). The recognition of women's, feminist, and gender studies' (WGFS) financial value can be essential to its institutionalisation, which is also often contingent on the (over) performance and income-generation of individual feminist scholars (Pereira, 2015, 2017). This can be read alongside the idea of a 'somatic crisis' (Burrows, 2012), or 'psychosocial and somatic catastrophe' (Gill & Donaghue, 2016, p. 91) in academia, characterized by stress, anxiety, depression, insomnia, guilt, insecurity, anger, loss, failure, and disorientation. Pereira analyses a contemporary academic 'mood of physical exhaustion, intellectual depletion and emotional despondency… a sick [academic] climate' (2017, p. 188). Here, pursuing the transformative projects of queer and feminist scholarship in contemporary UK HE begins to appear as an exemplar of what Berlant (2011) theorises as cruel optimism: an investment, attachment, or desire for a problematic object or way of life which threatens wellbeing; an 'attachment to compromised conditions of possibility' (Berlant, 2006, p. 21).

Occupying academic spaces uncritically can reproduce exclusionary, exploitative, harmful structures and practices that queer, feminist, and queer feminist scholars may seek to resist and rework (Breeze & Taylor, 2018). Queer and feminist academics are pressured to work instrumentally within the audited terms of the neoliberal, entrepreneurial, marketised university. As we write this introduction and work on this Special Issue we are simultaneously engaged in concurrent processes of 'accountability and development reviews', 'interim probationary reviews', 'three year career development planning', 'zoning exercises' and contested annual workload allocations. However, queer feminist academics are far from passive participants within these disciplinary structures, and the entangled sites of implication and investment in the institution is also the ground from upon which we negotiate, resist, and rework (Breeze, 2018; Breeze & Taylor, 2018). Queer and feminist scholarship continues to be thought of as a site of hope, possibility, and resistance (Res-sisters 2016) despite or perhaps because of a 'kinda subversive, kinda hegemonic' position in relation to 'the' university (Sedgwick, 1993, p. 15).

This introduction has not set out to define or delimit 'what counts' as feminist and/or queer scholarship, instead we hope the debate is continued and expanded between readers and the articles that follow. This Special Issue brings a range of related topics in the fields of feminist and queer scholarship in higher education together into interdisciplinary conversation, including: discomfort, vulnerability and authority in the queer feminist classroom; the agentic possibilities of queer educational desires; early career transitions in gender studies research; 'accidental academic activism'; and the post-work imaginaries of feminist trade unionism.

In 'Forging queer feminist futures through discomfort: vulnerability and authority in the classroom', Órla Meadhbh Murray and Lisa Kalayji consider how to put queer feminist politics into pedagogical practice. The authors use auto-ethnographic methods to explore discomfort in university classrooms, from their position as PhD students working as tutorial and seminar teachers in a UK university, and focus on experiences of 'coming out' (or not) as queer, and on how queer feminist early career scholars negotiate their own ambivalent and partial authority. They weave an argument which considers queer temporalities and orientations towards prefiguring a feminist future 'holding the tensions, contradictions, and discomforts of inhabiting the present and enacting the future'.

Vicky Gunn's article, 'Queer desire's orientations and learning in higher education fine art' considers how 'the desires which determine self-placing within the LGBTQI+ rubric orient learning', exploring the relationships between students' creative wills and the discipline of fine art. In doing so Gunn traces 'abrasions' between queer subjectivities and different forms of normativity, and argues that the tactics used by queer student artists can be analysed as a 'queer anatomy of agency'. This article prompts readers to re-think the connections between desires and disciplinary learning, and in doing so to think about the queer presences, and the present, in higher education.

Turning to future-orientated academic categories, in 'German early career scholars in gender studies: do networks matter?' Irina Gewinner focuses on the role of professional networks in the decision-making and career trajectories of early career scholars working in gender studies in Germany. Gewinner's article asks 'do networks matter' and considers how supervisory – and other academic – relationships shape the likelihood of entering into, and continuing with, an academic career. Early career scholars' 'motivations' for pursuing postgraduate study and careers in gender studies are put in further social context via a consideration of the interaction of career trajectories with the structure of doctoral programmes and the status of gender studies as a discipline.

In 'Accidental academic activism: intersectional and (un)intentional feminist resistance', Francesca Sobande develops an analysis of accidental academic activism, using auto-ethnography, extracts from her research diaries, and elements of creative practice. The discussion considers the (mis)identification of academic activists, as intersections of racism and sexism result in the 'presumed political' presence of Black women in academia. Alongside a consideration of the future-orientated 'neoliberal pressures to perform perfection', Sobande argues that using reflexive and creative methods to explore the contested relationships between academic and activist positions, we can better understand the parameters – possibilities and limits – of feminist activist-scholarship.

Finally, in 'Feminist trade unionism and post-work imaginaries' Lena Wånggren begins with feminist academics' unpaid teaching, research, and administration work, highlighting the gendered impacts of working conditions in the marketised university, with a specific focus on precariously employed scholars in UK HE. Wånggren discusses feminist trade union strategies and feminist ethics of care as responses to these working conditions, and draws on post-work and anti-work politics, as possible prefigurations of more inclusive, accessible and sustainable futures for higher education and for feminist union activism.

Together these articles are situated temporally alongside this editorial as written in a particular moment, 'we are writing in time, at a particular moment, which is partial and positioned and in place' (Back, 2004, p. 204). Likewise, these articles are written from differently classed-raced-gendered positions, just as we mobilise career categories – the early career academic, the established professor – that themselves articulate a temporal location in the academic career course (Breeze & Taylor, 2018). Writing in the moment brings with it an attendant failure to capture such a moment in its assumed totality, and in its multiplicity, just as with the future we need to ask which and whose educational futures are privileged when we speak with the definite article.

Failure is a useful object to think with alongside queer and feminist futurities, including those in being and becoming a feminist academic in the neoliberal university (Shipley, 2018). Compiling this Special Issue has involved a modest sense of hopeful investments and attachments to possible educational futures, making space for queer and feminist scholarship, contributing to broader epistemological and activist-academic projects. At the same time, we have recognised – and felt – failures in ways that accord with existing analyses, as when critical, queer feminist scholarship can be 'read as a failure, mobilized by the angry, emotional feminist academic, rather than her "neutral" "objective" "rational" un-emotional counterpart' (Taylor, 2013, p. 51). We join those who examine the generative potential in failing to live up to the impossible demands of the hungry university. Thinking about, and with, futures and fractures in feminist and queer education means thinking of generative 'failure' in another sense; the ways in which the transformational praxes of queer and feminist higher education are orientated to a future which is necessarily partial, flawed, and incomplete. In working on this Special Issue we are struck by how these tensions are ongoing, rather than resolved. So thinking back to the universalizing tendency found in imagined educational futures, and returning to some specificity we ask readers to consider their own investments and attachments to educational futurity as you read the articles that follow.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to all participants at the 2017 Educational Futures and Fractures conference, University of Strathclyde, and to the anonymous peer reviewers who provided rigorous and generous comment on each article in this issue. Thank you to all the authors for their work, and for submitting their articles to this issue. Thanks to the journal editors Cristina Costa, Mark Murphy and web publisher Eileen Murphy for their work supporting the special issue.

References

Acker, J. (2006). Inequality regimes: Gender, class, and race in organizations. Gender & Society, 20, 441-446.

Acker, S. & Armenti, C. (2004). Sleepless in academia. Gender and Education, 16(1), 3-24.

Acker, S. & Wagner, A. (2017). Feminist scholars working around the neoliberal university. Gender and Education.

Adams, R. (2018). Universities strike blamed on vote by Oxbridge colleges. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/feb/21/universities-strike-blamed-on-vote-by-oxbridge-colleges

Addison, M. (2012). Feeling your way within and across classed spaces: The (re)making and (un)doing of identities of value within Higher Education in the UK. In Y. Taylor (Ed.), Educational Diversity: The subject of difference and different subjects. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ahmed, S. (2012a). Embodying diversity: Problems and paradoxes for Black Feminists. In Taylor, Y. (Ed.), Educational Diversity: the Subject of Difference and Different Subjects. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ahmed, S. (2012b). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Ali, S. (2007). Feminist and Postcolonial: challenging knowledge. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30(2), 191-212.

Ali, S. Mirza, H., Phoenix, A. & Ringrose, J. (2010). Intersectionality, Black British feminism and resistance in education: a roundtable discussion. Gender and Education, 22(6), 647-661.

Arday, J. & Mirza, H. S. (Eds.). (2018). Dismantling Race in Higher Education Racism, Whiteness and Decolonising the Academy. Palgrave Macmillan.

Back, L. (2004). Writing in and against time. In M. Bulmer & J. Solomos (Eds.), Researching Race and Racism. Routledge.

Ball, S. (2003). The teachers' soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Educational Policy, 18(2), 215-228.

Berlant, L. (2006). Cruel Optimism. differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 17(5), 21-36.

Berlant, L. (2011). Cruel optimism. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bhambra, G. K., Gebrial, D. & Nisancioglu, K. (Eds.). (2018). Decolonising the University. London: Pluto Press

Breeze, M. (2018). Imposter syndrome as a public feeling. In Y. Taylor and K. Lahad (Eds.), Feeling academic in the neoliberal university: feminist flights, fights, and failures. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Breeze, M. & Taylor, Y. (2018). Feminist collaborations in higher education: stretched across career stages. Gender and Education.

Burrows, R. (2012). Living with the H-Index? Metric assemblages in the contemporary academy. The Sociological Review, 60(2), 355-371.

Dear, L. (2018). British University Border Control: Institutionalization and Resistance to Racialized Capitalism/Neoliberalism. The International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 17(1), 7-23.

Dinshaw, C., Edelman, L., Ferguson, R. A., Freccero, C., Freeman, E., Halberstam, J., Jagose, A., Nealon, C. S. S. & Nguyen, T. H. (2007). Theorising queer temporalities: a roundtable discussion. GLQ, 13(2-3), 177-195.

Edelman, L. (2004). No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Emejulu, A. (2018). On the problems and possibilities of feminist solidarity: The Women’s March one year on. IPPR Progressive Review 24(4), 267-273.

Gabriel, D. & Tate, S. A. (2017). Inside the Ivory Tower: Narratives of women of colour surviving and thriving in British academia. London: UCL IOE Press.

Gannon, S., Kligyte, G., McLean, J., Perrier, M., Swan, E., Vanni, I. & van Rijswijk, H. (2015). Uneven relationalities, collective biography, and sisterly affect in neoliberal universities. Feminist Formations, 27(3), 189-216.

Gill, R. (2010). Breaking the silence: The hidden injuries of neo-liberal academia. In R. Flood & R. Gill (Eds.), Secrecy and Silence in the Research Process: Feminist Reflections. London: Routledge.

Gill, R & Donaghue, N. (2016). Resilience, apps and reluctant individualism: Technologies of self in the neoliberal academy. Women's Studies International Forum, 54, 91-99.

Henderson, E. F. (2018). Feminist Conference Time: Aiming (Not) to Have Been There. In Y. Taylor & K. Lahad (Eds.), Feeling Academic in the Neoliberal University: Feminist Flights, Fights and Failures (pp. 33-60). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Hey, V. (2004). Perverse pleasures — Identity work and the paradoxes of greedy institutions. Journal of International Women's Studies, 5(3), 33-43.

Leathwood, C. & Read, B. (2009). Gender and the Changing Face of Higher Education: A Feminized Future? Open University Press.

Leigh, D. (2017). Queer feminist international relations: uneasy alliances, productive tensions. Alternatif Politika, 9(3).

Lipton, B. & Mackinlay, E. (2016). We only talk feminist here: Feminist academics, voice and agency in the neoliberal university. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Mahn, C. (forthcoming). Black Scottish Writing and the Fiction of Diversity. In M. Breeze, Y. Taylor & C. Costa (Eds.), Time and Space in the Neoliberal University: Educational Futures and Fractures. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Mahony, P. & Zmroczek. C. (1997). Class Matters: Working class women's perspectives on social class. London: Taylor and Francis.

Mirza, H. S. (2006). Transcendence over Diversity: Black Women in the Academy. Policy Futures in Education, 4(2), 101-113.

Mirza, H. S. (2015). Decolonizing Higher Education: Black Feminism and the Intersectionality of Race and Gender. Journal of Feminist Scholarship, 7/8, 1-12.

Muñoz, J. E. (2009). Cruising utopia: the then and there of queer futurity. New York: NYU Press.

Pereira, M. (2016). Struggling within and beyond the Performative University: Articulating activism and work in an "academia without walls". Women’s Studies International Forum, 54, 100-110.

Pereira, M. (2017). Power, Knowledge and Feminist Scholarship: an Ethnography of Academia. London: Routledge.

Pereira, M. (2018). Too tired to think: On (not) producing knowledge in the hyper-productive university. Talk at the University of York, February 2018. Retrieved from https://www.york.ac.uk/news-and-events/events/public-lectures/spring-18/too-tired/

Puwar, N. (2004). Space invaders: Race, gender and bodies out of place. Oxford: Berg.

Rahman, M. (2004). The Shape of Equality: Discursive Deployments During the Section 28 Repeal in Scotland. Sexualities 7(2), 150-166.

Reay, D. (1997). The double-bind of the "working class" feminist academic: the success of failure or the failure of success? In Mahony, P & Zmroczek, C. (Eds.), Class Matters: Working class women's perspectives on social class (pp. 18-29). London: Taylor and Francis.

Sedgwick, E. K. (1993). Queer performativity: Henry James's The Art of the Novel. GLQ, 1(1), 1-16.

Shipley, H. (2018). Failure to launch? Feminist endeavors as a partial academic. In Y. Taylor & K. Lahad (Eds.), Feeling academic in the neoliberal university: feminist flights, fights, and failures. Basingstoke: Palgrave

Skeggs, B. (1995). Women's studies in Britain in the 1990s: Entitlement cultures and institutional constraints. Women's Studies International Forum, 18(4), 475-485.

Southerton, D. (2003). 'Squeezing Time': Allocating Practices, Coordinating Networks and Scheduling Society. Time and Society, 12(1), 5-25.

Sparkes, A. C. (2007). Embodiment, academics, and the audit culture: A story seeking consideration. Qualitative Research, 7(4), 521-550.

Sullivan, N. & Simon, J. (2014). Academic Work Cultures: Somatic Crisis in the Enterprise University. Somatechnics 4(2), 205-218.

Taylor, Y. (2005). Inclusion, Exclusion, Exclusive? Sexual Citizenship and the Repeal of Section 28/2a. Sexualities, 8(3), 375-380.

Taylor, Y. (2013). Queer encounters of sexuality and class: Navigating emotional landscapes of academia. Emotion, Space and Society, 8, 51-58.

Taylor, Y. (Ed.) (2014). The entrepreneurial university: Engaging publics, intersecting impacts. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Taylor, Y. (Ed.), (2012). Educational diversity: The subject of difference and different subjects. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Taylor, Y. & Lahad, K. (Eds.). (2018). Feeling Academic in the Neoliberal University: Feminist Flights, Fights and Failures. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Taylor, Y. & Scurry, T. (2011). International and widening participation students' experiences of higher education, UK. European Societies, 13(4), 583-606.

The Res-Sisters. (2016b). "I'm an early career feminist academic: Get me out of here?" Encountering and resisting the neoliberal academy. In R. Thwaites & A. Pressland (Eds.), Being an early career feminist academic: Global perspectives, experiences, and challenges. London: Palgrave.

Thwaites, R. & Pressland, A. (2016). Being an early career feminist academic in a changing academy: Global perspectives, experiences and challenges Basingstoke: Palgrave.

University College Union. (2018). Home secretary changes rules to ensure migrant workers can take strike action. Retrieved from https://www.ucu.org.uk/article/9575/Home-secretary-changes-rules-to-ensure-migrant-workers-can-take-strike-action

Waller, R., Ingram, N. & Ward, M. R. M. (2017). Higher education and social inequalities: getting in, getting on and getting out. London: Routledge.

Footnotes

[*] Email: [email protected]

ISSN: ISSN 2398-5836

Copyright (c) 2018 Maddie Breeze, Yvette Taylor