Milton scholarship has been drawn to the work of Habermas as a way of grappling with Milton’s ideas about the public sphere, political debate and civic participation. Laura Knoppers’ paper does us a great service by summarising this literature as well as exploring complex issues around gender and the distinction between the public and private in both Milton and Habermas. There is certainly much of interest in the discussion around gender and Habermas’ take on the public sphere, a take that some have considered overly bourgeois and/or masculinist. Nancy Fraser’s article Re-thinking the public sphere is inevitably included and so it should, taking Habermas to task not only regarding gender but also for his neglect of social equality as a precondition of democratic debate.

Two other issues of note surfaced in my reading of the paper – the first relates to Habermas’ own desire to avoid artificial distinctions between the public and the private: for him, the two spheres were intimately connected – a case acknowledged by Knoppers:

Habermas’s model for the public sphere, it should be noted, from the beginning resisted a sharp dichotomy between public and private. The private persons who come together to debate in the public sphere are technically, in his model, still within the private realm, that is, apart from the state itself. In this way, even from the beginning, the Habermasian public sphere had the potential for critique of a public/private dichotomy that reinforced gender hierarchy and exclusion (Knoppers, 616).

The second issues relates to how the connections between Milton, Habermas and gender studies opens up our understandings of what the public sphere actually consists of, a sphere not so much physical as virtual in character:

As these recent studies indicate, more fully considering gender in discussions of Milton and Habermas opens up important new materials for analysis, including expansion of Eve’s role to that of reader and participant in rational debate. Habermas helps us to imagine the public sphere as a virtual space, a mode of thought and communication, a debate over and questioning of authority that was previously unexamined. Although Habermas himself does sometimes point to actual spaces – coffee houses in London and salons in France – there is much in his analysis to suggest that the public sphere is not a physical space (Bloch; Mah). This concept of public and private that is linked not with physical space, but rather, with a new kind of rational discussion and debate helps us to rethink the categories of private and public in Paradise Lost and to widen the range and impact of Eve as herself a subject who reasons, questions, and debates.

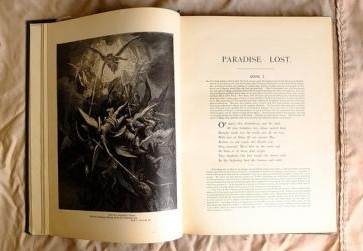

Knoppers turns to the Garden Scene in Paradise Lost to illustrate the existence of such a virtual sphere, one that traverses the divide between public and private:

On the morning of the fall, when Eve suggests working apart, citing the overgrowth of the garden and the need to accomplish more, free of distraction, she opens up a conversation that questions for the first time divine planning. What are the limits of their autonomy? Is each sufficient alone? If not, why not? The echoes of Areopagitica, as scholars have noticed, come back. Free choice and reasoning are virtues in the postlapsarian world. What about here? Adam and Eve together reason, debate, and discuss. If a “public sphere” opens in Eden in Paradise Lost, the separation scene would seem to be the place where it begins, with the consciousness of Adam and Eve that they are debating subjects (Knoppers, 620-621).

This take on the public sphere as manifested in the Garden of Eden provides a distinct contrast to the fall from grace experienced by the public sphere under late capitalism, at least as depicted by Habermas in the conclusion of The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (see a previous post on this). But given the emphasis on the virtual in his own work as well as the gender and Milton studies explored by Knoppers, a case could be made that the promise of the public sphere could potentially find its realisation in its modern digitised form. This is a big if of course, given the tendency of some web-based interactions to degenerate and infantilise. But if there is one tendency that the web shares with Habermas’ conception of the Public sphere, it is the lack of a sharp distinction between the public and the private. For better, or for worse?