Lately I’ve been reading Paul Ricoeur’s book The course of recognition, as I have a strong interest in all things relational. I came to Ricoeur’s work, however, long after I first encountered Charles Taylor, Nancy Fraser and in particular Axel Honneth, one of the reasons why he doesn’t figure much in my recent paper (co-written with Tony Brown) Learning as relational: intersubjectivity and pedagogy in higher education. This paper was an attempt to argue for a different understanding of the academic-student relationship, one that isn’t overly focused on consumerism and marketisation and instead adopts an intersubjective view of the teaching and learning context – here’s the abstract:

Lately I’ve been reading Paul Ricoeur’s book The course of recognition, as I have a strong interest in all things relational. I came to Ricoeur’s work, however, long after I first encountered Charles Taylor, Nancy Fraser and in particular Axel Honneth, one of the reasons why he doesn’t figure much in my recent paper (co-written with Tony Brown) Learning as relational: intersubjectivity and pedagogy in higher education. This paper was an attempt to argue for a different understanding of the academic-student relationship, one that isn’t overly focused on consumerism and marketisation and instead adopts an intersubjective view of the teaching and learning context – here’s the abstract:

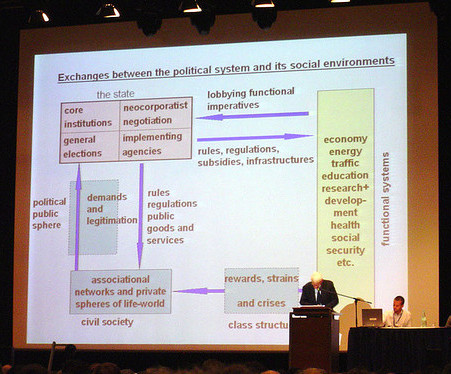

The decision to make the UK student population financially responsible for their own university education has major implications for the future of higher education provision. Chief among these implications will undoubtedly be a much stronger emphasis on the student experience, not least the experience of the teaching and learning environment. Given the increasing influence of consumerism on student identity, the distinct possibility exists that such notions of market-led accountability will be first in line to shape how the academic–student relationship is redefined and understood in future years. It is therefore an appropriate time to explore alternatives to such a narrow understanding of relationships – an understanding that inevitably tends to frame direct accountability in terms of economic exchange. It is argued in this paper that one alternative can be developed by exploring a more relational approach to HE pedagogy, and more specifically one that is based on a synthesis of critical theory and psychoanalysis. By emphasising the intersubjective nature of learning and teaching and the role of emotions in this regard, the paper argues that a relationally centred approach takes seriously questions of trust, recognition and respect at the heart of the academic–student relationship, while also making space for doubt, confusion and relational anxiety.

The combination of object-relations psychoanalysis and the linked concepts of latter-day critical theory is, I think, a promising avenue to explore when it comes to reconfiguring the higher education context. At the same time, such a task isn’t going to be completed in the space of one article, and looking back over the paper makes me wonder where the likes of Ricoeur and his take on recognition could contribute to future conceptual development. I’m still reading the book and there’s plenty of value in it, but I particularly liked his discussion of the nature of love in the context of mutual recognition (present or absent). He provides a helpful reminder of how Hegel used the word Trieb to explain what love actually is – i.e., ‘the desire of the desire of the other’. Taking this as a starting point, via detours through the work of Honneth and also Simone Weil, Ricoeur fleshes out this notion of love by stating that ‘lovers recognise each other by recognising themselves in models of identification that can be held in common’. A power ‘more primitive than desire’, love as Trieb brings together so many relational senses at once – a sense of worth, acceptance, acknowledgement, regard, respect and belonging – that its status as an object of desire in itself is inevitable.

But Ricoeur wisely balances this take on Trieb via its opposite – the absence of the desire of the other. This flipside of love is a painful experience, as to be unloved is to be disregarded, and to be viewed as undesirable, in Ricoeur’s (and Honneth’s) words, a painful form of humiliation:

Humiliation, experienced as the withdrawal or refusal of such approbation, touches everyone at the prejuridical level of his or her ‘being-with’ others. The individual feels looked down on and from above, even taken as insignificant. Deprived of approbation, the person is as if nonexistent.

The hatred of absence, of humiliation, of disregard, of others who refuse to offer desire, is also a powerful force in people’s lives, a force as worthy of investigation as that of love itself.

Now I might be going out on a limb here, but to talk about love and hate in the higher education context might be seen as somewhat controversial, so let’s be careful here – these words in this context refer to the love/hate of the presence/absence of recognition, as opposed to the concept of romantic love (I’m glad we cleared that up). And however people feel about using such emotive terminology (I’m not even sure I’m comfortable with it), Ricoeur’s take on mutual recognition does strike me as a potentially useful analysis for deepening the critical theory/psychoanalytic view of the academic relationship.

But this deepening certainly isn’t going to happen on a cold Monday evening in Glasgow, so that’s my lot for now – but if anyone does have a view on this, please, feel free to comment/get in touch – Mark