A study published by Deursen and Dijk (2014) provides a new angle on the Digital Divide debate which has often been guilty of a binary classification of technology “haves and haves not” (p, 14).

Placed in the Dutch context the research reveals that individuals from all social classes are now making use of the web. This contradicts arguments that the digital divide is directly related to high levels of economic capital, or lack of it. This is likely to be a direct result of new-ish policies that aim to make technology and broadband increasingly more affordable in Europe. So, with the “technology fix” sorted, what else are we missing?

When it comes to digital practices (and digital habitus), the history of social class division seems to reproduce itself on the online world. The authors report that individuals from a lower socio-economic status (and unsurprisingly with less education under their belt) are more likely to access the web to play games or engage in social interactions, whilst individuals from upper classes (and with higher levels of education) use the web mainly to access information and seek (professional) development opportunities.

In short, the study reveals the expected: simply put, people from upper classes seem to be able to strategise their activities online better. This unquestionably puts them at an advantage when compared to the online activities carried out by individuals in lower classes. The distinction herein presented is punctuated by a difference of (and in) practice(s). This is nothing more than a reflection of the cultural capital individuals embody and which they carry with them to the online world.

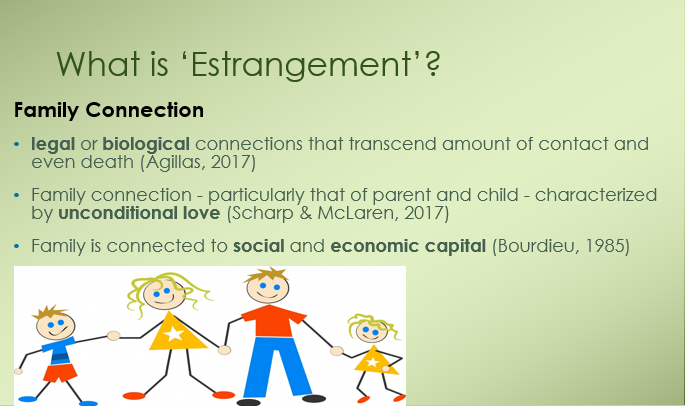

And so, even though the digital divide may well be shifting to differences in usage, when it comes to differences in social class, the digital divide only seems to be getting wider. In part, this comes as no surprise. Individuals transport their habitus from one field to another. The advantage of one group in relation to another is no longer in the technology they possess, but rather in the embodied cultural capital they transfer from the offline world to the online world. All of a sudden, the idea of ubiquitous access to technology no longer seems to provide an answer to the digital divide phenomenon. But Bourdieu (1986) seems to know where the issue lies. He reminds us that:

To possess the machines, [they] only need economic capital; [but] to appropriate them and use them in accordance with their specific purpose [they] must have access to embodied cultural capital, either in person or by proxy.

So the question remains: how can we narrow the digital divide gap? Can the introduction of digital literacies in the curriculum be a step towards a solution?

References:

Bourdieu, P. (1986). Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory of Research for the Sociology of Education (pp. 241–58). Greenwood Press.

Deursen, A. J. van, & Dijk, J. A. van. (2014). The digital divide shifts to differences in usage. New Media & Society, 16(3), 507–526.