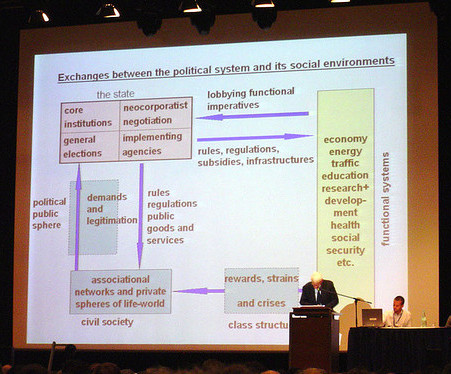

In his newest book, Freedom’s right: the social foundations of democratic life, Axel Honneth readily acknowledges his debt to Frankfurt School critical theory, particularly Habermas. He is arguably at his most Habermasian when discussing the pathologies of legal freedom, pathologies that revolve around the assorted tensions between communicative and instrumental forms of action:

What has been always regarded as one of the downsides of increasing legal codification is the fact that the juridification of communicative areas of life subtly compels subjects, both the directly and the indirectly affected, to take up an objectifying stance toward their highly individuated interaction (p. 90).

In order to illustrate the pathologies of juridification, Honneth refers to the plot of the 1979 movie Kramer vs. Kramer, starring Dustin Hoffman and Meryl Streep. Honneth has previous when it comes to popular culture references, so this shouldn’t be any surprise. But this is a particularly insightful reference, as it does a good job of explaining Habermas’ colonisation thesis and the peculiar janus face shown by the legal system:

The plot … represents the decisive diagnostic medium. Only at this narrative level does the film illustrate the process through which individuals are transformed into mere ‘character masks’ of the law. This transformation becomes particularly striking when Ted Kramer learns that his now separated wife has changed her mind and decided to fight for legal custody of their child after all. At this point, the husband, as if steered by an invisible hand, begins to calculate all his daily actions in terms of how they will affect the decision of the judge. After he is fired from his job, he takes a much lower-paid job just so that he can prove his ability to provide for his child by finding steady work; during the divorce proceedings, he perceives his son’s freak playground accident merely as having a negative effect on his own demands for custody. In fact, his entire interaction with his son increasingly becomes a public demonstration of parental care, love and affection, causing not only the male protagonist, but also the viewer to doubt whether his actions are an expression of true feelings rather than mere displays of good behaviour that can stand up in court (90-91).

The opportunity offered by the law in the form of negative freedom, according to Honneth, can easily turn ‘into a style of life’, In the case of Ted Kramer, the point at which legal opportunity turns into legal constraint occurs when the communicative experience of his lifeworld is gravely threatened by the steering mechanisms of the legal profession. And hence the pathologies of legal freedom – what law gives in one hand it takes away in the other.