Just published: Costa, C. (2014). Double gamers: academics between fields. British Journal of Sociology of Education. doi:10.1080/01425692.2014.982861

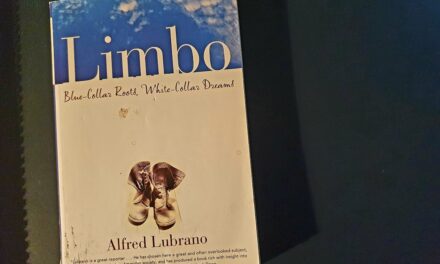

This is the third paper I have written from my Ph.D research. This paper reports on the dilemmas digital scholars face when placing their academic practices between two contrasting fields: that of academia, which regulates their practices, and that of the social web, on which the canons of academic knowledge production are challenged by distributed learning networks with a common mind-set.

The fieldwork took place just before the conclusion of the Research Excellence Framework (REF) whose results have coincidentally been released today. As such it is no wonder that REF played a very important role in participants’ narratives of practice. Exercises like REF were seen as detrimental of the digitation of HEIs, especially in its more radical forms; those that aim to open up the knowledge monopoly to the wider society not only with open access journals but also through other genres of knowledge communication and engagement.

In my Ph.D I looked at this aspect of the research data through a conflict lens that helped me illustrate the tensions between habitus and field, between the practices individuals developed online and those that are cultivated and recognised by the academy. For this paper however I decided to look at it from a different perspective, namely through the concept of doxa. In so doing, I looked at both the participatory web and academia as fields of action with distinctive rules and traditions.

Although research participants were avid advocators of digital scholarship practices, they were also aware that to remain relevant in their profession they needed to play by the institutional rules. This was more notorious in academics with a less established portfolio or those committed to go up the career ladder. However, it was clear that although they adjusted their practices to the institutional game, they were equally committed to not lose sight of their digital practices. This meant that they were playing by two different set of rules to fulfill both the institution’s expectations and their own aspirations.

As I reflected in the paper, rules serve the purpose of promoting the ambitions of a field. Bourdieu calls these rules the field of doxa that eventually become embodied in individuals’ practices as a collective belief. Doxa can does be regarded as an instrument of domination; of symbolic violence.

With this idea in mind, I started to ponder if the participatory web, as a social field, was also promoting doxic thinking. I came to the conclusion that that was the case. Academics commuting between the two fields transport the doxa of one field to the other through their habitus. The hope is to transform a more conventional academic habitus with their digital approaches. However, the economic and symbolic capital that academia possesses or aspired to – also through REF – determines its power over its agents, thus making it hard for its rules to change. The participatory web, on the other hand, operates on a more informal structure, in which participants’ practices are not prescribed, with the exception, of course, of the collective beliefs that are therein formed and shared.

This results in a ‘double gamer’ approach; a compromise that allows research participants to remain relevant in both fields while they attempt to change the academic practices of one field with the activities developed in the other.

What remains to be seen now is if in a post-REF period digital scholarship practices will finally make an impression on institutional regulations as its new doxa.

Could the next REF be a conduit to such transformation?