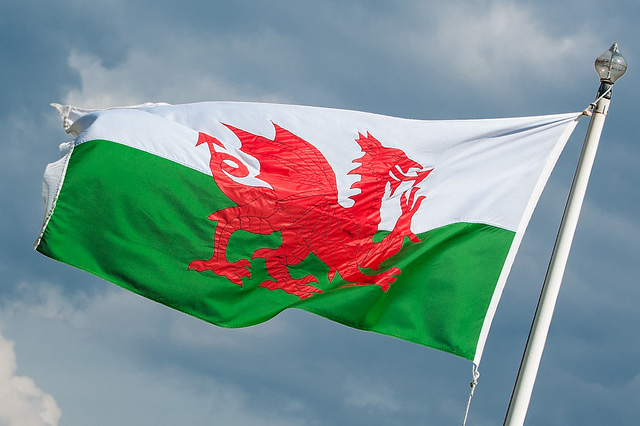

image by marcokalmann

The phrase ‘imagined community’ has taken on a life of its own in recent years but can be traced back to the publication in 1983 of the book Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Written by Benedict Anderson, a Professor of International Studies, Government & Asian Studies at Cornell University, it explore the ways in which nationalism and nationalist movements led to the creation of nations, or as the title puts it, imagined communities. The emphasis in the book is on the invention of nationalism, not as a political ideology akin to Marxism or Fascism, but rather as a socially constructed artefact based on cherished

ideas and sentiments about community solidarity and belonging. There was nothing inevitable about the rise of nationalism according to Anderson; its origins lay in the migration of Europeans to the Americas, in particular Creoles who had never been to the ‘motherland’ yet felt a deep connection to their ancestral home (in a time when travel was difficult at best). The rise of nationalism in Europe was a response to the imagined nationalism in the European diaspora, and the book argues that this then spread via colonialism to Asia and Africa. The grand irony of the book is that what in the end defeated colonialism and colonial power was itself an invention of Europe via the back door – a set of independence movements with a nationalist imagined community at their core.

The book itself avoids Eurocentrism, and instead is wide ranging and international in both outlook and evidence. There are plenty of

case studies from across the globe that build on the example of Creole culture in America. What is also of worth in the book is the argument about the power of shared media in the construction of national identities. Although in other ways critical of Marx’s legacy, Anderson is at his most Marxist in his account of the power of print capital and its powerful effects on identity and solidarity.

Anderson’s book, which is cited much more than it is read, should not be mentioned without discussing the numerous critiques that have been made of it. For a brief summary, see Howard Wollman and Philip Spencer, ‘“Can such Goodness be profitably discarded?” Benedict Anderson and the Politics of Nationalism’, in The Influence of Benedict Anderson, edited by Alistair McCleery and Benjamin A Brabon, Edinburgh: Merchiston, 2007:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/8de2tun7xxhlzbc/Wollman%20and%20Spencer%20-%20Can%20such%20Goodness%20be%20profitably%20discarded.pdf?dl=0