This is the title of a keynote I will deliver in September as part of the Symposium: Student Politics in Contemporary Higher Education – Theory, Policy and Practice. This is to take place in Durham University – below is the abstract of my talk. Hope to see some of your there, Mark

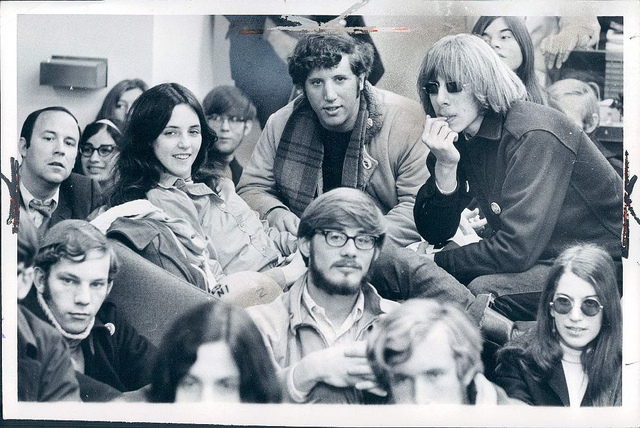

Social theory has a complex relationship with student politics and student protest. The events of 1968 are a case in point: while Jean-Paul Sartre supported the students at the barricades in Paris, over in Germany Theodor Adorno and Jürgen Habermas were critical of the revolts sweeping across universities, suggesting that radical student politics had elements of ‘left fascism’ that helped to undermine democratic institutions.

1968 is also the year often regarded as a turning point in continental social theory – a year in which the dogma of Marxist theory, especially in France, yielded intellectual territory to the postmodern turn and paved the way for the likes of Jacques Derrida, Hélène Cixous, Michel Foucault and Julia Kristeva. This shift introduced among other things a more dispersed analysis of power and its production through various social practices – of knowledge, culture, language, the body. The certainties of the revolutionary struggle for socialism became much less certain when the institutions of the state themselves (such as universities and schools) were seen as forces of domination in their own right.

This intellectual schism is still with us today in various forms, and both of these strands of social thought still vie for space when it comes to the politics of higher education – their diagnostic power can be seen for example in critiques of marketisation and consumerism that have fueled recent student protest across the UK. This paper will take a closer look at this theoretical debate, in particular by focusing on two key issues: the accountability of universities in a context of fiscal and political constraint; and the legitimacy of academic knowledge in a world of contested epistemologies.