In this interview, Mark Carrigan (@mark_carrigan) talks to Dr. Matt Dawson, Lecturer in Sociology, University of Glasgow. Dr. Dawson’s research has been primarily in the field of social theory, including questions of normativity, socialism and politics. Most recently this has involved looking at the history of ‘sociological alternatives’ (sociologists offering ideas for alternative societies). This includes the publication of a book entitled Social Theory for Alternative Societies (2016, Palgrave Macmillan) and a chapter on the lost history of sociological alternatives. Thinkers covered in the book include: Marx and Engels, Durkheim, Weber, Du Bois, Mead, Mannheim, Lefebvre, Marcuse, Selma James, Oakley, Dworkin, Giddens, Beck, Levitas, E.O. Wright, Burawoy and Bauman. More detsil on Dr. Dawson’s research can be found here.

In this interview, Mark Carrigan (@mark_carrigan) talks to Dr. Matt Dawson, Lecturer in Sociology, University of Glasgow. Dr. Dawson’s research has been primarily in the field of social theory, including questions of normativity, socialism and politics. Most recently this has involved looking at the history of ‘sociological alternatives’ (sociologists offering ideas for alternative societies). This includes the publication of a book entitled Social Theory for Alternative Societies (2016, Palgrave Macmillan) and a chapter on the lost history of sociological alternatives. Thinkers covered in the book include: Marx and Engels, Durkheim, Weber, Du Bois, Mead, Mannheim, Lefebvre, Marcuse, Selma James, Oakley, Dworkin, Giddens, Beck, Levitas, E.O. Wright, Burawoy and Bauman. More detsil on Dr. Dawson’s research can be found here.

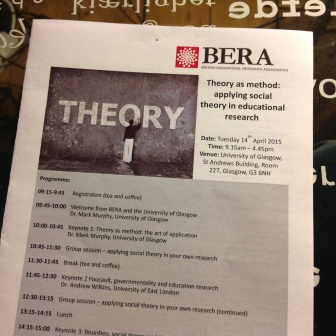

What is theory?

I feel like there are two answers I can give you here. One would be the formal, intellectual, answer. Theory is generalised statements about the social world which draw upon the diverse empirical findings of sociology. These statements can then be ways of making sense of this data and/or claims which the data hopes to ‘test’. In this sense then, theory has an intimate relationship with empirical studies and every sociologist who engages in the activity of making sense of the social world does, at some point in whatever form, draw upon theory.

I have no problem with this definition of theory. It is indeed what theory is, even if this is often what Stanley and Wise call (1990:24) ‘theory of a capital T’ where individual theorists, often of a select grouping, praised and their claims ‘enshrined in ‘texts’ to be endlessly pored over like chicken entrails’.

But, I don’t think it’s sufficient as a total definition of theory, since theory is also more fundamentally about a way of seeing the world. When we encounter theory and its concepts they will, hopefully, allow us to see something about the world we previously missed and give us a fuller understanding of the nature of the social world and how it works. This is the definition of theory which, when I teach, I draw upon. Good theory, when we are introduced to it, should be able to give us this new, expanded, way of seeing the social world.

Why is it important?

Well I guess my answer to this is kind of a tautological restating of the above. Since theory is about providing us with ways of seeing the world, it is important by giving us those ways. To give a bit of a broader justification to this, I’ve always enjoyed Bauman’s claim. In his book with Keith Tester, 2001’s Conversations with Zygmunt Bauman, Tester offers a concern often uttered by sociologists. Namely, that ultimately our work isn’t taken up more broadly and that ‘all’ we can do is perhaps change the self-understanding of groups such as our students. Bauman’s response is telling: ‘’Sociology cannot change anything except the self-understanding’?! What is this ‘except’ supposed to mean? Is not ‘changing self-understanding’ already a titanic task?! If only we could be sure that we are up to that task’ (Bauman and Tester 2001:156-157).

I think that’s why I find theory important. It allows us to change our self-understanding in the sense of our place in the world, how this society around us works and the possibility of different social forms. That’s important, if we accept (as Bauman, and I, would) that a situation in which people are aware of their social situation and able to critique it, is important. If you don’t think that’s important, theory is important in the sense that it allows sociologists to make sense of empirical findings. This is, I would note, also very important! It isn’t an either/or situation.

What role does it play in your work?

Most of my work is ‘theory’ work in that sense that I am discussing ideas put forward by other social theorists, their value and flaws. It is also theoretical in that it consists of evaluations/explorations of particular social theorists (notably Bauman and Durkheim). In this sense, my work fits within the category of what is today considered ‘theory’. I can’t claim much credit as to the originality of theory generation which I see among my colleagues.

Are there particular challenges which theorists face in career terms?

I think there are challenges. I have been immensely lucky when it comes to my career but I observe the challenges for my colleagues, especially younger scholars. I think the most significant challenge here concerns the relative paucity of funding for purely theoretical work, especially at an early career stage. This makes it difficult for people to carry forward any theoretical work post-PhD and find post-doc positions. In addition to this, at least from where I sit, it also seems funding for theory based PhDs might have contracted even from when I did my PhD (though I did mine unfunded, so perhaps that trend is longer running). Each of these pressures make those early steps on the academic ladder, often coming from funding, difficult to find.

When it comes to actually entering the job market, there will always be jobs for social theorists (partly because it is a topic which every sociology degree, and many others, will teach) but I’m not sure what percentage of those jobs are the ones departments/schools may invest in as permanent posts or consider it something which is coverable with temporary, teaching-heavy, contracts. Certainly, given the increase prominence with which questions of who might be able to submit an impact case study, the possibility of gaining funding and ‘knowledge exchange’ more generally, the powers that be may consider a social theorist a less attractive candidate for a job. I have been delighted when I see permanent lectureships for theorists (and, selfishly, when I see friends got those posts) but it would be interesting to know how common these are.

But, I would also sound a note of warning concerning the particularity of these challenges here. These pressures are of course things which impact all academics, not just theorists; they may be exacerbated for this group, but they’re not the only group. I’m sure many of my colleagues struggling through the run of short-term and teaching-heavy contracts would, quite rightly, be put out by the suggestions that somehow they were the ‘lucky’ ones against the ‘unlucky’ theorists (leaving aside the more difficult question of who would count as a ‘theorist’ in that division). The challenges theorists face are just a subset of the challenges most early career researchers face and I would want any battle against these challenges to rest on that universal basis, rather than about seeking to restore a position for a select group of ‘theorists’

What role do you see for theory in helping sociology negotiate the challenges it faces in the future? I’m thinking particularly of issues like the impact agenda in the context of British sociology.

This is a really difficult question and I suspect my answer will be insufficient. I think the first alarm bell I might sound is the idea that there would be a negotiation from ‘sociology’. This implies one of two things: a) that being a ‘sociologist’ however defined produces a Mannheimian thought-style which leads people to act in a particular way towards things like the impact agenda and/or b) that there is something innate to sociology, a set of values say, which produces a particular orientation towards the impact agenda. I don’t think either of these statements are true. There will be sociologists, theorists or not, who welcome the impact agenda or are indifferent to it. So, I think the possibility of some common negotiation position from ‘sociology’ is impossible. There will be differences, perhaps most notably around the distinction Goldthorpe once made between sociology ‘of the think tanks’ and ‘of the departments’.

That being said, I know where I stand in light of these pressures (strongly-against in my case). What role might theory have in challenging them? I’m not sure it has a particular unique position which separates it from other branches of sociology. It should seek to defend the value of a sociological perspective in and of itself as a way of understanding and critiquing the worlds in which we find ourselves. It shouldn’t succumb to any justification to defend this perspective in line of institutionally decided goals (such as whatever counts as ‘impact’ today) or passing policy fancy (one thinks here of the AHRC’s short-lived Big Society funding pathway, whatever happened to that?). This is what I would hope sociologists would do, stand up for the value of the perspective we call our intellectual home. We’ve been threatened before (if anything, I would suggest things were worse in the 80s) and it was through the combined efforts of particular sociologists seeking to defend the discipline and its value that we’re still here.

Will this happen? I don’t know, count me as part of the school who doesn’t think sociology is a predictive science. But, when I am feeling a bit pessimistic I turn to Durkheim who, in the 1890s, wrote the following: ‘even science has hardly any prestige in the eyes of the present day, except in so far as it may serve what is materially useful, that is to say, serve for the most part the business professions’. The impact agenda, and the associated forms it takes, is part of a long tendency, noted by sociologists (see also Victor Branford complaining about Universities which ‘put their faith in the primacy of money over goods and life’ in 1919) throughout its history of seeking to reduce knowledge to profit. We (by which I mean those committed to a particular idea of what sociology can be for) fought it before and we’ll fight it again.