2018 has been a strange year. Actually, the world has become a particular strange place to me since 2016. Although I recognise that for other people – depending on their own context – the world may have always been strange, some of the latest events in the ‘West’ have left me fearful of our democratic future, one that I thought I had conquered, or that at least I had been welcomed into. I will explain it through my own life experience. But succinctly, I see before me History unfolding; a History not too different from that of the previous century, yet different enough for people not to recognise it. It is an unsettling history in which gender, race, and religious struggles have been “disguised” and replaced with speeches of economic solutions and national identity. It is a struggle of power that is destroying the democratic progress made in the last 70 years or so.

This account is my own perspective. But it is also a perspective that has been developed with the support and readings of theory that helped me to understand current social phenomena and the practices therein developed. My argument is that more than ever we need to read and engage with such literature so that we can consciously evaluate what is happening around us and how and why our own attitudes – or lack of it – shape the environment we live in. I talk from a perspective of a ‘Western culture’, the culture that shapes my practice.

I was born and raised in a country that had just come out of a long and damaging dictatorship regime. I was born and raised under assumptions that women and men were equal and free, but yet that equality and freedom was measured differently. That difference, as felt in practice and in the flesh, always outweighed the similarities. Although I was always aware of such differences, I hardly ever had the vocabulary to express what it meant or how it made me feel, but I knew it wasn’t right. Such gender conflicts are often accentuated and reinforced by other classic struggles such as those related to social status, ethnic background or religion. Living in a rather monolithic country where religion was concerned, it meant that religion became invisible to me. The same could not be said about race. Racism was a practice I witnessed in my growing up, but one that was not directed at me and so I did not feel it in the flesh. My circle of friends and acquaintances were pretty much a homogenous bunch that unknowingly helped one another to detach themselves – myself included – from the racism that many people, I am sure, have felt and experienced. I now realise that it was a privilege position to be in, a position I was unable to recognise at the time. However, the injustice that was closer to home to me – and the one that aggravated me the most – was not the one related to social class, but the one related to my gender position. I never understood why the responsibility to behave appropriately fell on me, why I should have less freedom than boys, or why if the financial option to study was there just for one of us, then my brother should take it over me (as it was told to me on different occasions by different people, as a way of saying ‘you should feel lucky’). These are just some examples emerging from the same issue, the issue that boys can and should and girls can but should not exercise their rights fully. I was blessed that even though my life was clouded by some of these perceptions and practices I was allowed to pursue my education at University, probably unaware of what it would really mean.

I cannot say that my degree made me particularly aware of the intersectional issues that afflict social phenomena – although such degree was ripe for such ‘cause’ as I later found out by having access to other higher education systems – but it certainly gave me some tools to work with. Such tools came early in the day when I borrowed one of my landlady’s book and read Simone de Beauvoir’s Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter . It was a reassuring narrative, one that I could resonate with despite the geographical and time distance between me and when and where the author wrote such account. It made me realise that such struggles are universal. It was a revelation to me. It was also an invitation to continue to be in full control of my duties and responsibilities, but also aware that I do have rights as do other people and that these should be respected at all times and under all circumstances.

It was however when I started to engage with social theory studies that I acquired appropriate language to express what I already knew but was unable to communicate fluently. Very succinctly and in a lay language, for example, Pierre Bourdieu’s work taught me that our day-to-day practices (and attitudes) are often shaped by invisible, historical ‘forces’ that inform the way we think or approach a situation without us necessarily understanding why. Sometimes these ‘forces’ are disguised or recognised as ‘tradition’ and therefore go unquestioned. However, taken for granted practices may conceal the interests of a certain group or individual; interests that more often than not do not benefit those who help produce them. Yet, when one does not question why we do things or behave in a certain way – just because it was always like this – we risk perpetuating unfair behaviour without realising it or even meaning to do so. Unquestionable practices serve the purpose of preserving a certain order, where each individual is put in their place according to a perception of value. For example, it is not uncommon that when not knowing their gender the title of a Professor or a CEO be attributed to a man rather than a woman. I myself have been guilty of making that linguistic mistake. Yet, it is not only a linguistic mistake, it’s a perception that I have incorporated in my thinking system because of the realities I have experienced. Another example, is the fact that sometimes we praise people who have not gone to university but turned out successful business people. Take Richard Brandson or Victoria Beckham as examples. We attribute their success to their hard working. Yet, we forget the (hidden reference to their) social status that allowed them to make such choices in the first place.

My recent engagement with the work of Axel Honneth has also allowed me to perceive the world from a new lens. Honneth notes that recognising the value of all human beings in an equal fashion paves the way ‘to a good life’. He goes on to highlight 3 pre-requisites

- The need human beings have to be cared for;

- The need for individuals to be given equal legal rights so that they can freely participate in society and;

- The need to be conferred “social worth” in that all individuals should be appraised for their idiosyncratic features rather than discriminated on the basis of their differences.

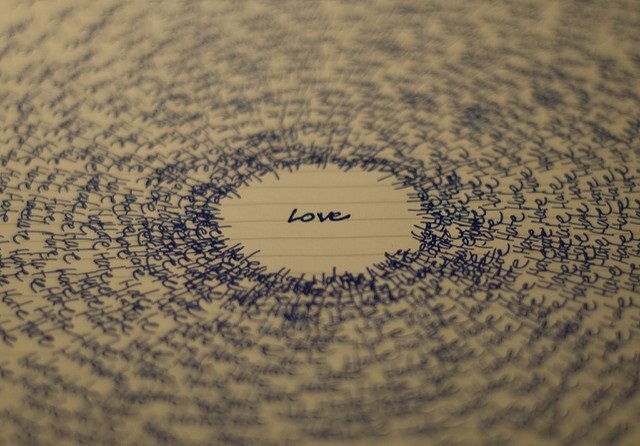

These three principles – which he calls Love (in its broader sense), Rights and Solidarity respectively– when applied to daily-practice contribute to the self-realisation of the individual as a recognised human being. The opposite results in a sense of disrespect in which people are denied of their humanity.

This post is, to a great extent, motivated by the latest socio-political events that have marked the world this month alone and that totally and utterly ignore the project ‘of a good life’ by cultivating a set of unquestioned practices that can only be deemed unethical. For example, Trump’s mocking of Dr Ford for her testimony is a clear example of disrespect for a fellow individual in all its 3 forms: Love, Rights and Solidarity. Trump dehumanised Dr Ford by mockery when he played the card that women are traditionally weak, when in matter of fact what Dr Ford did was an extreme act of bravery. More surprisingly, but not less shocking, is probably Women’s support for Cristiano Ronaldo as part of a rape allegation (and subsequent condemnation of the woman involved) on social media, where traditional assumptions of women’s respectable behaviour are used as arguments against the recognition of the accuser’s complaint. The examples above show that recognition is still an aleatory practice, one that conceals the interests of certain groups or individuals. What we have witnessed in the last weeks shows that we keep opening up inequality gaps by allowing engrained and unethical practices to carry on in plain sight, sometimes consciously (the Trump Case), sometimes unconsciously (The Ronaldo case, I want to believe). It is the unconsciously aspect that I mostly struggle with, because it means that people are unable to ‘see’ the structures that shape and condition their thinking and practices, thinking and practices that will condition them too. This is where I believe engagement with social theory ideas can help. Understanding how the social world works can aid us in the process of making sense of the ways (mechanism) that impel us to think and act ‘this and that way’.

Cristina will it be possible ever to finish completely the gender and religious struggle issue for forever?

Gender and religious issues are not too easy to be solved within a short period of time, but I think modernity will change the trend very soon.